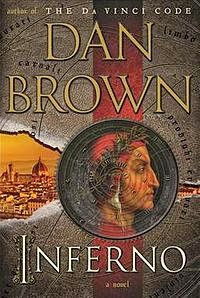

Some may have heard of the recent Dan Brown novel, Inferno, which is based on the first volume of Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy. In it, Robert Langdon travels about Italy to finally discover that the Catholic Church is ruining the world by encouraging overpopulation! Once again, Dan Brown drops "secret knowledge" on millions of unenlightened westerners (stay tuned for another post on JPII vs. The Da Vinci Code).

Instead of giving Dan Brown undeserved attention in this post, my focus is much moreso on Dante Alighieri, JPII, and the Virgin Mary. Most notably from JPII's comments and meditations on Dante in placing Mary as the apex of the Divine Comedy, especially in his Address: "At a Reading of Dante's Divine Comedy 08/31/97". Rather than focus on hell, as Brown does in his Inferno, JPII chooses to emphasize "Paradiso", and more specifically, Mary's overarching influence from heaven:

In the grand scene presenting man’s search for salvation, the Poet assigns a central place to Mary, 'humble and higher than creation', the familiar and sublime image of the woman who sheds light on the parable of the final ascent, after having supported the traveler’s tiring journey. What a consoling vision! Almost seven centuries later, Dante’s art evokes lofty emotions and the greatest convictions, and still proves capable of instilling courage and hope (http://www.fjp2.com/us/john-paul-ii/online-library/speeches/13833-at-a-reading-of-dante-alighieris-qdivine-comedyq-august-31-1997)

"Vision" is the word used to describe Mary in Paradiso, much like that of St. John the Evangelist in the book of Revelation. Furthermore, it is a "consoling vision", in stark contrast to the despair of the Inferno and difficult climb of Purgatorio.

Recall that just prior to Paradiso, Dante presents Beatrice as the crown of beauty, truth, and goodness. In a way, Beatrice prepares Dante to meet Mary, helping him to repent of his sins in the last few cantos before his ascent to "Paradiso". JPII captures Dante's joy to finally meet the Virigin Mother, calling her both "familiar and sublime" as Dante finishes his "tiring journey". It is as though Dante had already encountered aspects of Mary in Beatrice, explaining the 'familiarity'. Likewise, the 'sublimity' requires purity of heart to behold, which is why Dante had to repent of all that was not worthy of meeting the Theotokos. In notes on this topic, the University of Texas at Austin provides a detailed explanation of Dante's painful purification in his Purgatorio:

Examples of chastity and lust are provided by the penitents themselves as they walk within a raging fire on the seventh and final terrace of Purgatory. The spirits--at least those who desired partners of the opposite sex--cry out words spoken by Mary at the 'annunciation' when she asks how, not having sexual relations with a man (virum non cognosco [I know not man]), she will give birth to Jesus (25.127-8; Luke 1:34) [http://danteworlds.laits.utexas.edu/purgatory/09lust.html].

Mary is understood to be the example par excellence of those who upheld chastity and temperance in their lifetimes. In turn, Mary gives way to the rightful Lordship of her Son, as was so often communicated by JPII with his motto "totus tuus". His intention in devoting himself to Mary was precisely to be given over to Jesus, and although not explicitly stated by Dante in the Divine Comedy, this same theme is implied in the text.

Perhaps that is what is so effective in Dante's work, namely, the implication of God's presence throughout the epic poem but in such a hidden and surprising way as to attract both believers and non-believers into reading it. I remember friends reading, by their own free will, the Inferno in highschool because they said it was both "scary and fascinating". Little did they know that it touched on the faith and virtue needed for them to meet their Maker at the end of their days! Furthermore, the poem humbly places readers within the worldview of 'man's search for salvation', making some mistakes with Limbo and political judgments, but by and large staying true to Catholic understanding of the afterlife, especially in regard to the purification for sins before the beatific vision of God. Lastly, it successfully synthesized all of classic literature prior to Christ into a common patrimony (personified by Virgil) pointing to the revelation of the Blessed Trinity and salvation.

1) He fell in love with a child-hood friend, Beatrice, at nine. She was his muse even after her death in 1290, inspiring his first poem in 1294.

2) He began a military/political career in 1295 with the pro-papal Guelf party

3) He marries and has four children

4) The Guelfs split in two in 1300, into "whites" (pro-papal) and "blacks" (anti-papal) with Dante joining the latter

5) He is exiled from Florence, but later hailed poet laurete of Italy

6) Dies at Ravenna, 1321

Compare Dante's life choices amidst political upheaval, war, and papal corruption with Karol Wojtyla! In some ways they are similar: poets, citizens of countries at war, etc. Yet, they are very different as well: married man vs. priest, soldier vs. laborer, anti-papal vs. pro-papal. Imagine if Wojtyla had been outspoken in his criticism of Pope Pius XII for being neutral during WWII! Or for not doing more for refugees in the Vatican! It wasn't as though there were insufficient reasons to question/accuse the Church during the second world war. He certainly had his "Virgil" to thank in both his father, captain Wojtyla, and mentor: Cardinal Sapieha. Yes, Karol Wojtyla took a narrower road to Paradise than Dante Alighieri--and that "made all the difference!"

To conclude then, in Dante Alighieri we have a Catholic genius not to be confused with Dan Brown's depiction in Inferno, but more appropriately ranked with the caliber of JPII. Likewise, we have two men with lifelong devotions to the Blessed Virgin Mary, meeting precisely in their love of her as the crown of creation.

I deeply hope that Dante is resting in peace with the assurance of an ecstatic gaze on the beatific vision, including the beauty that created his beloved Beatrice.

*Update (This from a series on Purgatorio by Dreher):

Dante, like all the medieval intellectuals, believed in what you might call “number mysticism.” In the premodern metaphysical vision —a vision still embraced by philosophical Traditionalism; a very good, easily accessible presentation of this is in Prince Charles’s book Harmony — anyway, in the premodern metaphysical vision, the entire cosmos is shot through with divinely given order, and meaning. We can read the order and harmony of the world, and see in this the expression of God’s nature. This is a topic that is far too rich and complex to get into in this blog series. The important thing to know is that Dante incorporated this understanding deeply into the bones of the Commedia. Writes Prue Shaw:

Dante’s is a world where the number three seems to be a key to understanding reality in many of its fundamental aspects. The numerical pattern three-in-one is built into the very structure of things, a medieval version of what modern thinkers call a “fractal.” (Fractals are self-similar patterns: at whatever degree of magnification one uses, one sees the same pattern reappearing.) It is perhaps not surprising that Dante used the principle of three-in-one to structure his imagined world and the poem which celebrates it. What is astounding is how successfully he did so.

The Commedia as a product of human making — a man-made work of verbal art — was designed by Dante to embody the three-in-one principle. With satisfying symmetry, it does so both in its overall structure and in its individual component parts. The poem has three sections — Inferno, Purgatorio, Paradiso — which constitute one poem, the Commedia. The basic building black from which it is constructed is the terzina, or tercet, a single metrical unit consisting of three lines. Dante invented this metrical scheme, and by so doing made three-in-oneness a part of the very fabric of his poem.

There’s more. The tercet form Dante invented goes like this: aba bcb cdc. The entire poem is written this way; you can’t tell it in the English translations, but in the Italian original, the entire poem is linked in a chain of verse — this to express Dante’s metaphysical view that all reality is linked in a great chain of being. The pilgrim is learning how important it is to pray for the souls of the dead in Purgatory because we are all part of one community, one reality, in God. By extension, he’s learning how the human community is supposed to be united in harmony, by love, because we really are all brothers.

But there’s more to Dante’s structuring. Again, Prue Shaw:

The mirroring of patterns in the poem from overall structure to individual metrical unit goes even further. Because each line of the poem has eleven syllables, each tercet has thirty-three syllables, matching the thirty-three cantos in Purgatorio and Paradiso. Inferno has an extra canto, which functions as a preface to the whole work, making a total for the poem of one hundred cantos, the perfect number. (The perfect number is ten squared, ten itself being a perfect number, or so medieval mathematicians thought, because it is the sum of 1 + 2 + 3 + 4. So the poem is not just a verbal artifact but a mathematical one as well.

Cont'd

The medievals believed in the concept of habitus, which is to say the personal culture and worldview one carries in one’s head as a result of how, where, and among whom one lives. Our habitus shapes us; even when we have left people in our habitus behind in our journeys through life — and indeed, in the Commedia, Dante is propelled relentlessly forward, and repeatedly told in Purgatorio not to look back — the people from Dante’s habitus as a Tuscan of the High Middle Ages are unavoidably part of his habitus, even if they define the sins he’s trying to overcome. Dante the pilgrim has to go down into Hell so he can go up into Heaven. We pilgrims may have to go back to our past in some sense, to confront our personal histories, so we can go forward to a future that is more holy and peaceful.

Cont'd

"What Virgil offers us, symbolically, is a circle instead of Dante’s line, with man’s soul trapped in an inexorable cycle of births and deaths, undergoing an endless chain of one 'inferno' and 'purgatorio' after another. 167

Michael C. J. Putnam Materiali e discussioni per l'analisi dei testi classici No. 20/21 (1988), pp. 165-202

I will look most closely at Dante’s version of Anchises, as they take shape in Paradiso 15 and especially in Purgatorio 30, in the characters of Cacciaguida and Virgil. Dante’s Virgil, like Aeneas’ father, can accompany his protégé only so far in this complex quest. I will examine in particular the parallels and differences in these limitations set to the father-figure as guide. 169

The irony is, of course, that Aeneas’ action is one of the most Illiadic moments of the epic with Turnus wearing Pallas’ sword-belt standing in for Hector in Patroclus’ armor…The ending of the Aeneid lacks the fulfillments that bring the Illiad to a conclusion, the ransoming of Hector’s body and the lamentations and funeral that complete at once a life and a poem. 177

As we move from Aeneas’ epic and Virgil’s text to the Divina Commedia we change from tragedy of pagan darkness (and, I would add, from the dissonances implicit in Virgil’s pessimistic cyclicality) to the ‘comedy’ of Christian revelation (the Commedia as a type of Novum Testamentum) and the grace of its splendid acts of completion, in the concentrated focus on the Paradisal rose. We make the larger transitions metonymically in the smaller textual metamorphoses of Cacciaguida from Anchises (and, in part, the Sibyl) to God the Father, and of the pilgrim from Aeneas, entrapped finally in resentment, to a Christ figure who will suffer immediate earthly ‘inferno’ only to perform his own act of redemption for Florence by the endurance of his poetry." 190